As more asset managers begin to integrate environmental, social, and governance criteria into their investment strategies, the need for data and disclosures not typically found in traditional financial reporting has increased. Although corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosures were somewhat rare until recently, investors are coming around to the belief that analysis of a company’s ESG risks is just as important as understanding a company’s financials. Greater transparency into nonfinancial, material risks has tremendous value for both consumers and investors, but the value of the information that gets reported can occasionally be suspect.

To meet consumer and investment demand for this type of data, issuers tend to respond with CSR reports, alternatively called sustainability reports. The Global Reporting Initiative, an international standards organization that has developed one of the most comprehensive frameworks for CSR and sustainability reporting, defines the spirit of a CSR report as “a report published by an issuer about the economic, environmental and social impacts caused by its everyday activities.” They go on to suggest that such reports should include an organization’s values and governance policies, as well as demonstrate its commitment to a sustainable global economy.

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) also has created a framework — the Materiality Map — to help investors and institutions identify industry specific concerns that should potentially be addressed in a CSR report.

Government Requirements Though CSR reporting in the United States is voluntary, it is mandatory in the European Union for companies with greater than 500 employees. The SEC has explored how to improve reporting and disclosure by soliciting public comments about sustainability disclosures, but also announced in October 2017 that the comprehensive package of proposed changes to corporate disclosures and reporting did not include ESG disclosures, according a report from the Governance & Accountability Institute. Regardless, 85% of companies in the S&P 500 issued CSR Reports in 2017, up from just 20% in 2011, it added.

Concurrent with the rise of CSR reporting, questions have emerged regarding its true utility; CSR reports may more closely resemble marketing materials than financial statements, and while clear reporting frameworks such as the GRI’s exist, much of the data companies provide can be cherry picked.

In fact, a 2016 PwC survey revealed that nearly three-quarters of investors are neutral or somewhat dissatisfied with ESG reporting practices. As Robert Gutsche, Jan-Frederic Shulz, and Michael Gratwohl note in their paper Firm-value Effects of CSR Disclosure and CSR Performance, “most CSR disclosures have more than 200 pages and contain information that is connected only loosely to CSR performance.”

There is currently little in the way of assurances that investors are getting the true information they need to make truly informed investment decisions, and companies may benefit solely from the appearance of CSR activities; as Gutsche notes, when it comes to CSR reporting “words currently speak louder than actions.”

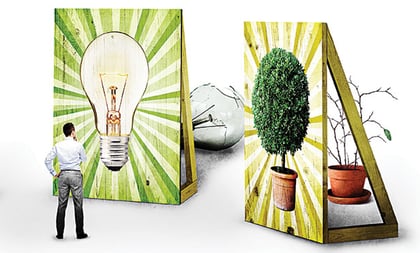

CSR Reporting: A Potemkin Village? Taking a cynical view, it could be argued that some CSR reporting resembles the deceptive construction of a Potemkin Village — a tale told of Grigory Potemkin setting up false fronts of villages to please Empress Catherine of Russia during her travels. In this case, playing to the demands of investors without stringent guidelines for reporting creates opportunities for companies to play up any good corporate behavior — regardless of its true impact — while minimizing the bad.

Gutsche found that “the mere disclosure of CSR activities may be interpreted as good CSR performance and mislead investors in their judgments of the potential long-term risks of their investments.” Further, “both CSR disclosure and performance affect firm value, but the relative effect of CSR disclosure is larger than the total effect of the individual dimensions of CSR performance.”

The fact that a company’s reputation may have little to do with true CSR impact is disconcerting. But if not CSR reports and ESG scores, then what should investors be looking at in their investment process?

Case Study: CSR Reporting in the Banking Industry One example of a CSR Potemkin Village can be observed within the banking industry. Banking is a complex and largely opaque business, with many of its product lines — such as commercial and consumer lending — employing a “black box” underwriting process. The lack of transparency makes the risk profiles and underlying financial incentives of banking products nearly impossible for most investors to grasp, and we are acutely familiar with how underhanded practices — like stated-income or no-income subprime lending practices —directly led to the global financial crisis. Determining the quality of a bank’s product line and the character of its management team is not an easy task.

There is information available to investors that cannot be manipulated by a bank, however, and that allows an investor to gain true insight into business practices. Litigation trends provide one way to track a bank by business segment or product division over time.

The presence of past, ongoing, or pending lawsuits points to risks and future liabilities that may be bubbling underneath the shiny surface of bank marketing. Legal costs, whether they are from legitimate or frivolous claims, also can eat up a material segment of a bank’s income.

Though legal costs among the top 10 U.S. banks have declined by 56% in the past five years, they still represent an estimated $8 billion, according to The Business Journals. Litigation expenses are far from trivial, and they are also highly unlikely to be reported within the pages of a CSR Report.

In 2017, Bank of America (BofA) was recognized by Euromoney as the World’s Best Bank for CSR. This was the second time that BofA earned the award, having received Euromoney’s inaugural award in 2015.

RobecoSAM, a global trailblazer in sustainable investing, also has lauded BofA by ranking it in its 2018 Sustainable Yearbook and thus including BofA in its select list of 21 high-performing global banks.

March 26, 2019 at 01:00 PM

March 26, 2019 at 01:00 PM